Words of notice: This is an article I wrote for Gekko. Many thanks for their consent to sharing this story here.

On Serverless, FaaS and Infrastructure as Code

It has been a few years now that Serverless as a concept changed the shape of our Clouds. What started off as a logical step, a new tool after the advent of container technologies became a subject in and of itself.

However, let us define a boundary first: this post will be concentrating on a major domain of Serverless which is the Function as a Service, also known as FaaS. The title of this article avoids mentioning “Serverless” for this reason; Serverless is a superset of FaaS. Without entering too much into details, Databases as a Service -DBaaS- solutions such as DynamoDB belong to Serverless since they share the same aspects: they allocate and consume resources when necessary, scale up and down seamlessly and are highly available by definition.

FaaS is a concept that took off when major cloud vendors announced their solutions in 2015~2017. The tooling is still a bit rough around the edges but there is certainly a way to be creative today. FaaS does not drift much from classic development practices since the idea revolves around operations and execution rather than pure software development. Speaking of operations, here is a question: what if functions could be written and deployed along with companion services in different environments, right from a terminal? That is the promise behind tools similar to AWS’s CloudFormation -or CDK for the adventurers- or Hashicorp’s Terraform.

Even though Terraform is rapidly evolving in a breaking fashion, it is a strategic technology today: multi-vendor, actively supported, with a large community and user base. It is possible to abstract the infrastructure to leverage the strengths and unique features of each cloud provider! In addition, the community is such that most of the ground–laying work is there and waiting for the technical teams.

CloudFormation and CDK chose a different direction: they are tightly integrated with AWS in such a way that configuration can be visualized, and outside changes tracked. Plus, it seamlessly integrates with existing infrastructure and develop it with TypeScript, JavaScript or Python and soon with Java and C#/.NET. Like Terraform, these tools are in rapid development and regularly receive more features and services.

Abstraction layers

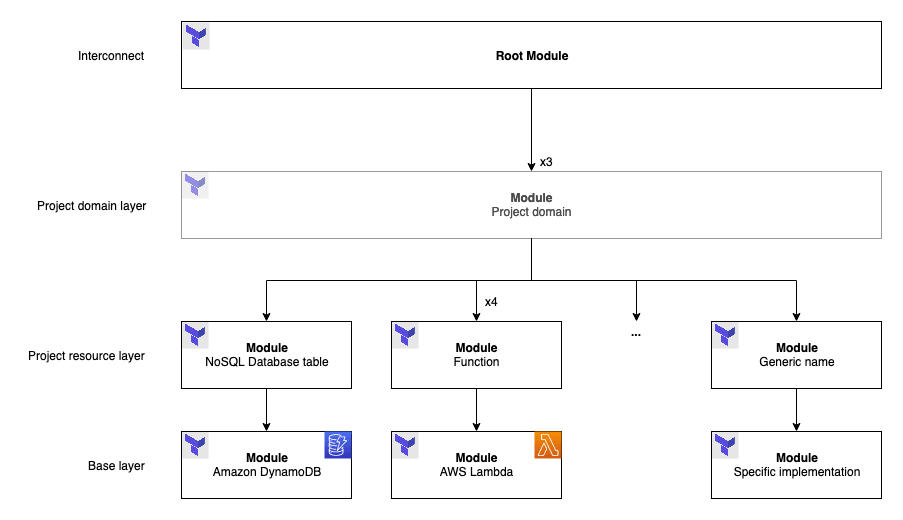

Figure 1: Basic Terraform abstractions

The infrastructure code in the next section is layered and each abstraction layer removes complexity from the resource configuration logic by making simple decisions. An example Terraform project structure may look like this:

- Base layer: contains generic resource code, could be abstracted away in a dedicated Git repository, S3 bucket, etc. and reused across projects;

- Project resource layer: sits on top of one or multiple resources, includes project assumptions and simplifies the outer layers;

- Optional project module layer: uses one or multiple project resources along with broader project assumptions to create a cohesive module that could be replicated by the outer layer. Beware, though: as of Terraform 0.12, for_each is not supported for modules;

- Interconnect: the root module, which will basically manipulate inputs and outputs. Its role is to hide the complexity of the stack by handling its outermost interactions.

In this architecture, the flows of information are limited to suit the needs of each layer, in a principle of least privilege fashion. This structure and our knowledge of Terraform can enable technical teams to create and deploy their own functions with minimal friction.

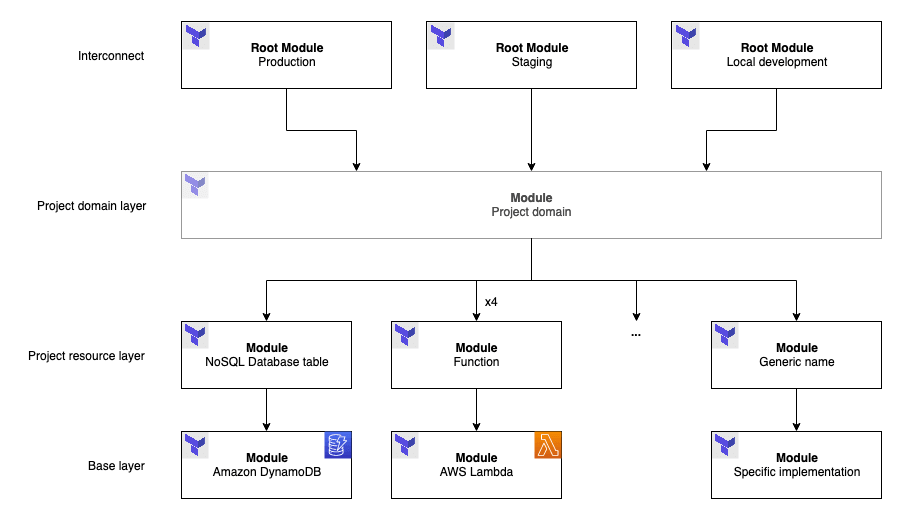

Figure 2: Using different root modules

Fortunately, pieces fit into place! Root modules are the entry points that define the resources to provision and their dependencies. Situations such as A/B testing scenarios or simplified environments for testing or development purposes can benefit from this architecture. In any case, the root module relates to the definition of the Interconnect layer.

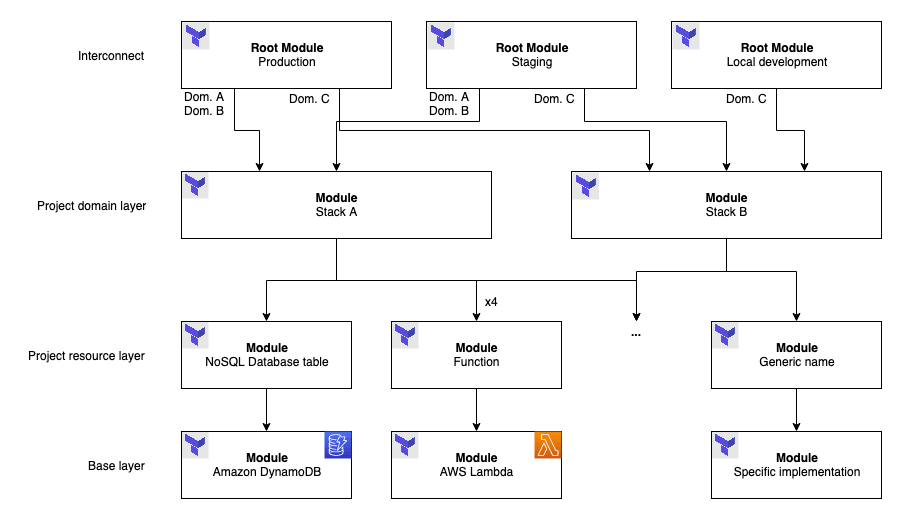

Figure 3: Stacks and environments multiplexing

If there is repetition in the resources to provision, such as multiple business domains with each its own dedicated API Gateway, Functions, etc. then the Project module layer comes into play and can be used to define where the Functions are located and which dependencies they need to run. This is not easily manageable with Terraform 0.11 but becomes a breeze starting with Terraform 0.12 and its richer type system. In any case, the resource layers structure can help. Just remember that the use of for_each structures within modules is not allowed yet, which limits uses requiring iteration on virtual resources.

However, remember that Terraform relies on declarative languages, therefore everything must appear explicitly otherwise resources may not be re-provisioned in the case of configuration changes. In addition, you may never need to go that far and at this point, splitting your stack into multiple sub-stacks could make your deployment safer. We will explore this subject in a follow-up post.

After all this theory, how about a demonstration?

Demonstration

The need

The demonstration will consist of a Create Read Update Delete API, which will be lean and run only when it is required to. The backend of the application will provide the logic for resource management. The items can be stored in a database that allows for custom properties in the object representation.

For this scale and need, API Gateway + Lambda is a generally accepted combination.

Repository structure and considerations

The code of this demonstration resides in the following repository. Keep in mind that this code is only meant for demonstration purposes and may not be used in a project without prior review of its contents.

The repository follows this structure:

/

|- api/

| - .json

|

| - application/

| | - lambdas/

| | - <lambda-name>/

| | | - index.js

| | - <other lambda files>

| |

| - layers/

| - <layer-name>/

| - nodejs/

| - node_modules/

| - <layer files>

|

- infrastructure/

| - modules/

| | - global/

| | - <provider>_<service-name>

| | |- outputs.tf

| | |- resource.tf

| | - vars.tf

| |

| - project/

| - <module-name>

| | - outputs.tf

| | - resource.tf

| - vars.tf

|

- origins/

| - ci/

- local/

- main.tf

This structure is standard and aimed at efficiency and semantics. A pathname should give the context necessary to

understand what a user is reading or editing. Here, the pathname

projectname/infrastructure/modules/project/function/outputs.tf refers to the outputs of the project module that

handles function creation related to the infrastructure of the project named projectname.

In this structure, the origins directory contains the Terraform root modules. The use of magic constants is not

prohibited as long as they refer to the behavior of the Infrastructure as Code. In addition, resources can be abstracted

by placing them in different files or modules. Both options are ideal whenever there is a need to reduce or hide the

apparent complexity of the provisioning process.

Resources

What would a resource look like in this demonstration? Here is the example of a function dependency. The directory structure of the function dependency modules is the following:

/

- infrastructure/

- modules/

| - global/

| - aws_lambda-layer

| | - outputs.tf

| | - resource.tf

| - vars.tf

|

- project/

- function_dependency

| - outputs.tf

| - resource.tf

- vars.tf

The names of these modules are different. That is a semantic form of decoupling: it means function_dependency may leverage AWS Lambda Layer or any alternative implementation. In every case, the project module separates the actual resource from the root module.

outputs.tf and vars.tf contain outputs and variable blocks and are always present, even if they are empty. This

structure is common practice. resource.tf files are the interesting part of this architecture:

# infrastructure/modules/project/function_dependency/resource.tf

locals {

dir_path = "../../../application/layers/${var.name}"

output_package = ".out/${var.name}.zip"

}

# Generate the archive

data "archive_file" "package" {

type = "zip"

source_dir = local.dir_path

output_path = local.output_package

}

module "resource" {

source = "../../global/aws_lambda-layer"

name = var.name

package = data.archive_file.package.output_path

compatible_runtimes = ["nodejs10.x"]

}

The project resource layer sets the software stack runtimes, generates the archive and creates a relationship between the layer name and the function dependency location.

# infrastructure/modules/global/aws_lambda-layer/resource.tf

resource "aws_lambda_layer_version" "resource" {

filename = var.package

source_code_hash = filebase64sha256(var.package)

layer_name = var.name

compatible_runtimes = var.compatible_runtimes

}

Something that might not come as surprising though, is the length of the file that will manage the resource. In the present case, it will only compute a hash of the package to deploy. This module could be versioned and stored in any Terraform source to be reused in future projects.

Testing the solution

The major advantage of abstractions relying on technology features is that they are as simple as using the technology

itself. From one of the root modules, it is manageable to replay the construction of its related infrastructure, from

terraform init to terraform destroy!

For instance, here is a trace of a terraform apply in the moduled origin of the repository:

moduled> AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID="********************" \

AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY="********************************" \

AWS_DEFAULT_REGION="*********" \

terraform apply

[…]

module.dep-crud.data.archive_file.package: Refreshing state...

module.fun-employee.data.archive_file.package: Refreshing state...

module.fun-employee.data.aws_region.current: Refreshing state...

An execution plan has been generated and is shown below.

Resource actions are indicated with the following symbols:

+ create

Terraform will perform the following actions:

# module.dep-crud.module.resource.aws_lambda_layer_version.resource will be created

+ resource "aws_lambda_layer_version" "resource" {

+ arn = (known after apply)

+ compatible_runtimes = [

+ "nodejs10.x",

]

+ created_date = (known after apply)

+ filename = ".out/crud.zip"

+ id = (known after apply)

+ layer_arn = (known after apply)

+ layer_name = "crud"

+ source_code_hash = "Jl1Gec0KfG2zq1m90olI4qCaeKU7BASzIWCA6KJ9uiM="

+ source_code_size = (known after apply)

+ version = (known after apply)

}

[…]

Plan: 9 to add, 0 to change, 0 to destroy.

Do you want to perform these actions?

Terraform will perform the actions described above.

Only 'yes' will be accepted to approve.

Enter a value: yes

module.dep-crud.module.resource.aws_lambda_layer_version.resource: Creating...

module.dep-crud.module.resource.aws_lambda_layer_version.resource:

Creation complete after 5s [id=arn:aws:lambda:*********:************:layer:crud:1]

[…]

Apply complete! Resources: 9 added, 0 changed, 0 destroyed.

The trace is no different from what one gets to see when using Terraform.

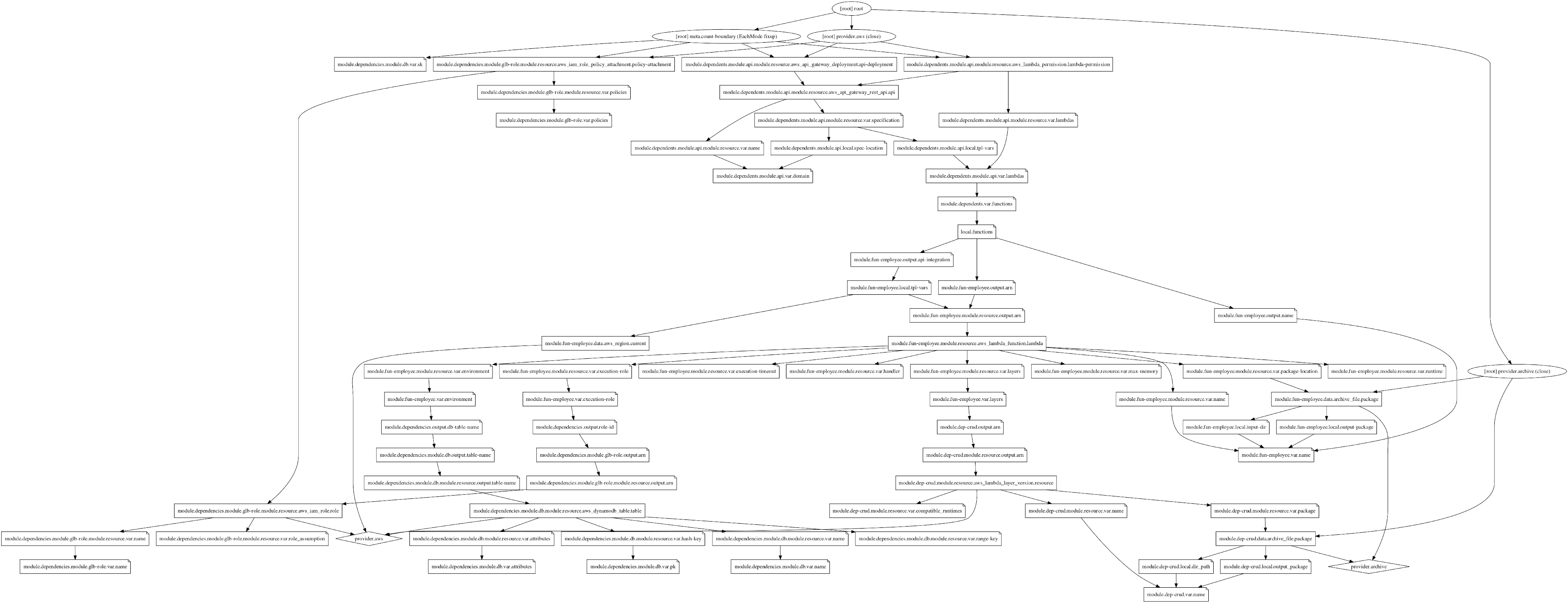

Figure 4: The Graphviz output of terraform graph

Generating a capture of the resources and their dependencies is recommended. Use terraform graph and a visualization tool for that purpose.

The result

Now that the infrastructure is covered, what would a custom Function and dependency look like?

module "lay-crud" {

source = "../../modules/project/function_dependency"

name = "crud"

}

module "lbd-employee" {

source = "../../modules/project/function"

name = "employee"

execution-role = module.glb-role.arn

layers = [

module.lay-crud.arn

]

environment = {

TABLE_NAME = module.ddb.table-name

}

}

That is all that is needed in this architecture. Creating the self-service FaaS is now equivalent to documenting this syntax, isolating Functions and dependencies for clarity and getting technical people started with Terraform. The rest of the infrastructure is provisioned once and only Functions and dependencies that change are re-provisioned, making iterations faster.

Furthermore, IDE extensions can invoke Functions painlessly, otherwise it could be conceivable to leverage the infrastructure and provision additional services such as an Amazon API Gateway, which URL could be displayed after each deployment.

Limits

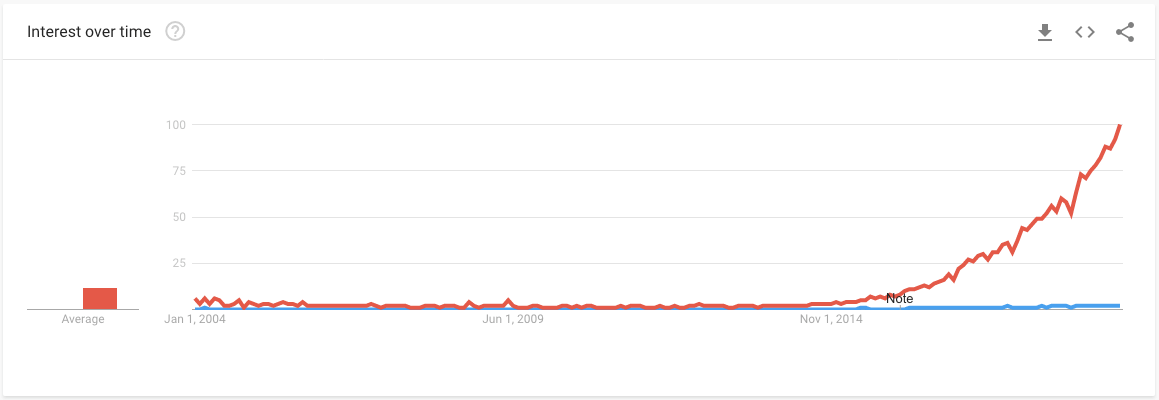

Figure 5: Google Trends on “Infrastructure as Code”

According to Google Trends, Infrastructure as Code is a novel concept that took off roughly at the same time Cloud vendors expanded their offerings. Automation did exist before, though the growing complexity of new architectures called for new, more powerful tools.

Figure 6: Red is “Terraform”, Blue is “Infrastructure as Code”

Remember that Terraform is still young, has imposed a few breaking changes and will still do in the forthcoming years. Terraform evolves along with its providers, features are frequently added and code breaks.

Regarding the architecture presented in this blog post, getting started with such ideas requires general knowledge of

Terraform and Infrastructure as Code. Nevertheless, once the base code for the software stack is coined and understood,

creating and destroying resources becomes second nature and the technical team can get productive. The learning curve

will be flattened as features arrive in the next versions, such as dependencies between modules and for_each syntax in

modules.

The achieved gain in productivity may be counterbalanced by the loss in flexibility. Indeed, the amount of conventions and magic mixed in with an infrastructure have a negative impact on maintenance, in the long run. Moving to an opinionated infrastructure locks down the possibilities offered by the tools, including with their updates and frustrates when a component needs to change.

Finally, generalization can lead to operational expenses and inefficiencies as each application and project is unique. One may find themselves applying a suboptimal stack on a project and missing the need.

Conclusion

More than a demonstration, this post expresses an invitation to consider infrastructure from a different perspective. Structure, semantics, conventions, abstraction. Tools and ideas at your disposal are plentiful, depending on your objectives.

There is no doubt that evolutions in that space will expand the possibilities of Cloud providers, development teams and technical landscapes in general. We are on the verge of a revolution and we are building it ∎